The Big Question

Although it appeared to be a massive failure, my first success as a Peace Corps volunteer was after two months of living in my community.

My Associate Peace Corps Director (APCD) gave all education volunteers the suggestion to hold a meeting with the School Governing Body (SGB) at each school to get an idea of what projects I could work on for the next two years. SGBs are similar to school boards, except each school has one instead of each district, as it is in the United States. They could also be compaired to PTAs, as the SGBs consist of parents of the attending students, teachers, and the principal.

My first attempt at this assignment was a meeting scheduled with the SGB at Phokwane Primary. I planned to facilitate a discussion using what we in the development business call the appreciative inquiry approach.

There are two basic approaches to development I'm familiar with. The first is needs based. A group or organization enters a community or organization and ask "what do you need?" The answer might be a clinic, a school, mosquito nets, medicine, etc. The organization then provides that need and, (usually) seeing their job as completed, leave.

The second approach is based on building a community's capacity to grow and improve on their own. The group or organization is asked by the development organization "what do you excel at? When is your organization most successful and a beacon in the community?" From there, they are asked what they would dream their organization or community could become, to invision their potential. An action plan is created and it is caried out. The process is cyclic.

Both of these approaches have their benefits. A community can not improve if its members are dying from mosquito bites. Likewise, a community cannot become self-sufficient if they are indefinitely receiving outside assistance.

Using tools provided to us during our training, I prepared questions to ask the parents using a method called participatory analysis. This line of questioning would help me learn more about the community and the feasibility of starting certain projects at certain times.

I arrived at 9:30 for the meeting scheduled at 10:00 which started at 11:00. It was what I had expected, and had brought a book, but was too nervous to read. My Sepedi was not yet at a point where I could use it to ask the kind of questions I had planned, and I've had poor experiences with white, English speaking individuals facilitating a room of black South Africans - the history of apartheid is still very present. Participants have been emotionally beaten down for the majority of their life. I wouldn't be quick to participate in a discussion lead by my former oppressor either.

My principal introduced me to the group. Sweat was running down by back, though it was not a particularly hot day. Mr. Madihlaba had struggled to get their participation during his part of the meeting, so I was particularly apprehensive about my chances of a successful discussion.

I began asking about the seasonal calendar, if there were times of the year when community members were more or less available - were they planting or harvesting at certain times of the year and less likely to be available to assist with community projects?

Educators talk about wait time. If you're willing to wait, usually you'll get an answer. This is true 99% of the time. So I asked the question and then I waited.

And waited.

Unfortunetly, one percent is still one percent. And people in Africa have been waiting a long time. With a nervous chuckle, I cut to the chase.

"What is it about Phokwane Primary that makes it such a great school? Why did you choose to send your children here instead of Thotaneng or one of the other area primary schools?"

I asked this while all around us the walls were crumbling. The classroom two doors down had its roof blown off in a storm four years ago and had never been repaired. Across the school yard, a classroom was unattended because its teacher was busy at the SGB meeting. I waited.

"The discipline is good," a parent said.

Finally, a response. I pushed her further.

"What specifically about the discipline is good? The punishments? The behaviors that are disciplined?" The head of department translated my questions.

I waited.

"The teachers discipline well."

I didn't know where to go. Maybe with more follow up questions I could have reached an answer that pointed us somewhere. Maybe I was too nervous, spoke too much English, and possessed too little experience. I moved on. We identified some possibilities. A teacher mentioned a garden. The meeting ended with the agreement that we could try the discussion again in January - but the meeting never happened. We ate lunch, and I went home disappointed.

The next morning I rode my bike to Phokwane with the hope of meeting with Mr. Madihlaba, debriefing the meeting, and then I had scheduled to observe some teachers teaching their classes.

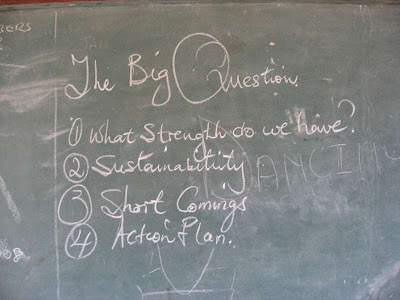

I parked my bike in an empty classroom and found the notes for the School Management Team (SMT) meeting on the board.

|

| From The Big Question |

Mr. Madihlaba had modeled the administration meeting off of my discussion.

All the teachers were in a faculty meeting that morning. I missed out on observing the classes because the teachers were planning. The next day the school yard was plowed and seeds were planted. The teachers made a garden to suppliment school lunches with vegetables.

|

| From The Big Question |

Not the improvement I wanted to see, but what I wanted was unimportant. It was the improvement the teachers wanted. And though the garden is currently being eaten by insects, it is still one of the most tangible signs of my arrival in this village.

No comments:

Post a Comment